Snow Tutorial

Last modified 2009-11-26

- Getting and Installing Snow

- Building Snow from source (optional)

- The Snow REPL

- Basic Concepts

- Layout

- Event handling

- Embedding Snow

- Data Binding

- What's more?

Getting and Installing Snow

You can download the latest Snow binary distribution from http://common-lisp.net/projects/snow/. It contains Snow and all its dependencies in a single Zip file. Since Snow can be used both in Lisp and Java applications, procedures for installing it can vary in each of the two cases.

Java applications:

simply make sure snow.jar and all the jars in the lib/ folder are in the classpath of your application. Snow uses JSR-223 and is built with Java 1.6, so that's the minimum Java version you can use. However, it should be possible to run Snow on 1.5 as well, but you'll need to recompile both Snow and ABCL from sources with a JSR-223 implementation in your classpath. See the Embedding Snow section below for details about using Snow inside your Java application.Lisp applications:

- Snow come prepackaged with ABCL 0.16, and it wraps the ABCL launcher with its own, that makes sure to load Snow prior to your application. So you can just follow the procedure for Java applications above, and use the snow.Snow class in place of org.armedbear.lisp.Main as the main Java class to launch, e.g. via a shell script. The only difference is that, when launched with no command-line switches, Snow will pop up a GUI repl. You can pass a dummy --no-gui-repl switch to inhibit that. If you are new to Java, the classpath is a list of search places that the JVM uses to resolve classes (think asdf:*central-registry* if you will). It can be set with the environment variable CLASSPATH or with the -classpath command line switch to the java bytecode interpreter (the 'java' command). It is a list of directories and/or .jar files, separated by a platform-dependent character (':' on Linux, ';' on Windows, I don't know about Macs). So for example, you can launch Snow on Linux with '

java -classpath snow.jar:lib/abcl.jar:lib/binding-2.0.6.jar:lib/commons-logging.jar:lib/miglayout-3.6.2.jar snow.Snow'.

- Also, Snow has its own version of Cells built in. It is a random, but fairly recent version from CVS, with some fixes to make it run on ABCL. I'm looking forward to having those fixes merged with trunk, so you'll be able to freely update Cells independently.

- Last but not least, Snow is built with ASDF, so if you are brave enough you can extract the contents of snow.jar (it is a regular zip file), it will create a directory tree full of .lisp source files, fasls and compiled Java classes (.class files). You will then be able to load Snow with ASDF using your own version of ABCL and/or Cells, provided you still meet the requirements about the classpath for Java applications. (there are two .asd files, one in snow/ and one in snow/swing).

Currently Snow, when run from the jar, requires a temporary directory to load itself; make sure your application has write permissions on your OS's tmp directory. Snow should automatically clear its temporary files when the application exits.

Building Snow from source (optional)

Snow is built using the Ant program (a Java make-like tool). You can get it from <http://ant.apache.org/>. To obtain the source code for Snow, either download a source release from the project page or, if you want the latest & greatest stuff, follow the instructions at <http://common-lisp.net/faq.shtml> to checkout it from the SVN repository. Once you have the source in a given directory, cd to that directory and issue the command ant snow.jar to build Snow. ant snow.clean removes all compiled files.

The Snow REPL

Being based on Lisp, Snow offers a REPL (read-eval-print-loop), an interactive prompt that allows you to evaluate arbitrary pieces of code. If you launch Snow through its main class (snow.Snow) with no command-line arguments, it will show a window containing the REPL (which is nothing more than a wrapped ABCL REPL). It should print

SNOW-USER(1):

SNOW-USER is the active package (namespace), (1) is the line number of the REPL. Now, the obligatory hello world:

(frame (:title "Snow Example")

(button :text "Hello, world!"

:on-action (lambda (event)

(print "Hello, world!")))

(pack self)

(show self))

Evaluating this will show a window containing a single button which, when pressed, will output "Hello, world!". The terminology should be familiar to Swing developers. Actually, the output from the button will NOT go to the REPL, but to the OS console instead; I'll explain this later, please ignore it for now.

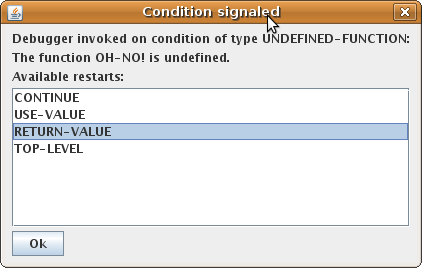

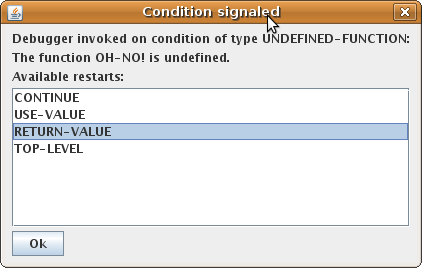

The REPL is great for experimenting: the code you input is immediately executed by an interpreter. You can also compile your code, either on the fly in the REPL or from a file; this is outside the scope of this tutorial, but you can find more information in any decent tutorial or book about Common Lisp (I suggest the free ebook Practical Common Lisp by Peter Seibel, available at http://gigamonkeys.com/book/). However, experiments sometimes go wrong; if you make a mistake - for example, evaluating an unexisting function - you will end in the debugger. Try typing the function call

(oh-no!)

- you should see something like this:

The restarts are the actions the system can perform to recover the situation; this is an important feature of Common Lisp, worth studying by itself. You'll always be able to choose the TOP-LEVEL restart, which will bring you back to the REPL.

You can quit the REPL (and terminate the application) any time by closing the REPL window, or by typing (quit)1.

Basic Concepts

As you can see from the previous examples, Snow code consists of a tree of widgets; nesting in the code means nesting in the widget hierarchy, for example:

(frame (:visible-p t)

(panel (:layout "wrap")

(label :text "1")

(label :text "2")

(label :text "3"))

(panel ()

(label :text "4")

(label :text "5")

(label :text "6"))

(pack self))

Creates a frame with two children, both panels with 3 children each - one has labels from 1 to 3, the other from 4 to 6.

You can set the properties of the widgets using keyword-value pairs like :visible-p t which means setVisible(true) (-p is a suffix traditionally used in Lisp to name predicates, T is the canonical true value). Containers must have their properties set in a list after the widget name -

(panel (...here go the properties...) ...here goes the body...)

- the list serves to separate them from the body. Non-containers have no body and thus their properties do not require to be wrapped in a list: (label ...here go the properties...)

How does this work?

The Snow API consists of a set of macros that can be used to declaratively construct a tree of widgets. These macros are designed in such a way to make the tree structure of Lisp source code closely mirror the GUI widget tree structure (in the general case). The macros expand to code that uses a functional interface to create widgets, however it is not recommended to use this functional API directly since it depends on the context established by the macros.

The aspects of such context of interest to the user are:

lexical variable self

Holds the current widget being processed. Example:

(frame ()

(print self))

will output something like:

#<javax.swing.JFrame ...frame.toString()... {identityHashCode}>

special variable *parent*

Holds the current parent widget. When *parent* is non-nil, any widget created through a macro will be automatically added to the container referenced by *parent*. All Snow widget macros process the forms in their body in the following way:

- if the form is a list, its car is a symbol, and this symbol has a property named widget-p, then the form is wrapped in a

(let ((*parent* self)) ...) i.e., it is evaluated in a dynamic context where the parent is the widget created by the macro.

- else, the form is wrapped in a

(let ((*parent* nil)) ...), i.e., it is evaluated in a dynamic context where no parent widget is defined (and thus widgets created by the form are not added to any widget).

These rules make the nesting of Snow widget macros work in an intuitive way:

- a widget defined at the top level in the body of another (container) widget w will be added to w. Example:

(frame () (panel ())) will result in a frame with a panel child.

- widgets appearing in code in the body of another widgets, but not at top level, will not be added. Example:

(frame () (let ((p (panel ()))))) will result in a frame with no children, and will create an "orphan" panel.

Snow provides operators to alter this default behavior:

(dont-add form) will always execute form in a dynamic context in which no parent widget is defined.(add-child container child &optional layout-constraints) will force child to be added to container, even if container is not the value of *parent*.

widget id

Additionally, all container widget macros support a pseudo-property called id which can be used to bind a lexical variable of choice to the widget locally to the macro body. Example:

(frame (:id foo)

(print foo))

will output something like:

#<javax.swing.JFrame ...frame.toString()... {identityHashCode}>

Layout

By default, Snow uses MiG Layout as the layout manager to organize components inside a container. When you create a component that will be automatically added to *parent* by Snow, you can use the pseudo-property :layout to specify (as a string) additional information for the layout manager. If you use add-child, instead, you have to pass this string to add-child as its last optional parameter (I hope I can fix this inconsistency). Here's a quick cheat sheet of the constraints you can use with MiG Layout: http://www.migcalendar.com/miglayout/cheatsheet.html (look for "Component Constraints").

You can use another layout instead of MiG: to do so, use the layout-manager property of the container. The values you can pass are:

- a keyword (supported ones are

:default, :mig, :border, :box) to select the layout manager by name; the names refer to layout managers available in Swing;

- a list whose car is one of the symbols above, and whose cdr is a list of the arguments passed to the layout manager (e.g.

(list :box :y) to have components be laid out in a vertical stack);

- a Java object which can be used by Swing as a layout manager (e.g.

(new "java.awt.FlowLayout")).

Event handling

Certain widgets can trigger events on certain types of user actions. These events can be handled by user code. Event-handling callbacks can be set using properties named :on-event-name (for example, :on-action for handling clicks on buttons, or ActionEvents in Swing/AWT parlance). Currently extremely few events are supported! I'll add new ones in future releases.

A callback for an event is either a Lisp function with a single argument (the event object), or an appropriate native Java event handler for the event (e.g., an instance of java.awt.ActionListener).

Events happen on a dedicated thread (in Swing's terminology, the EDT - Event Dispatching Thread). That's why, in the Hello World example, the string got printed to the console and not to the REPL! In fact, the REPL has its own dynamic, thread-local context, which rebinds the value of *terminal-io* to a stream that reads and writes on the REPL; the event, instead, is run in another thread, which doesn't have access to this context, and thus uses the global value of *terminal-io*. If you want to capture the value of a dynamic variable from the thread that creates the event handler, you have to explicitly do so like this:

(button :on-action (let ((tmp *some-thread-local-variable*))

(lambda (event)

(let ((*some-thread-local-variable* tmp))

...do stuff...))))

Embedding Snow

Snow can easily be embedded in a Java application by using JSR-223. The snow.Snow class has some static methods that can be used to load some Snow source code from a .lisp file (or classpath resource), or to obtain an instance of javax.script.ScriptEngine which you can use for more advanced stuff (e.g. compiling Lisp code, or calling specific Lisp functions). When embedding Snow to define (part of) the application's GUI, it is recommended that you modularize the Snow code in functions, which you'll call from Java to obtain the GUI components:

file.lisp

(in-package :snow-user)

(defun create-main-frame (&rest args)

...snow code...)

MyClass.java

...

Snow.evalResource(new FileReader("file.lisp"));

JFrame mainFrame = (JFrame) Snow.getInvocable().invokeFunction("create-main-frame", args);

...

Data Binding

Keeping the GUI state in sync with the application objects state is generally tedious and error-prone. Data Binding is the process of automating the synchronization of state between two objects, in this case a GUI component and an application-level object. Snow supports several kinds of data binding, and it uses two libraries to do so: JGoodies Binding on the Java side and Cells on the Lisp side.

General concepts

There are two general ways to bind or connect a widget to some object's property: one is by using the :binding property of the widget, letting the framework choose which property of the widget to bind, e.g. the text property for a text field; for example:

(text-field :binding (make-simple-data-binding x))

the other is to provide as the value of a widget's property an object representing the binding, as in

(button :enabled-p (make-simple-data-binding x))

this will connect the specific property of the widget with the user-provided object or property.

Types of data binding

Snow supports several types of data binding; some are more indicated for Lisp applications, others for Java applications.

- Binding to a variable. Syntax:

(make-simple-data-binding <variable>)

This is the simplest form of data binding: you connect a widget's property to a suitably instrumented Lisp variable. Such a variable must be initialized with (make-var <value>), read with (var <name>), and written with (setf (var <name>) <value>). Example:

(defvar *x* (make-var "Initial value"))

(setf (var *x*) "new value")

(button :text (make-simple-data-binding *x*))

- Binding to a Presentation Model. Syntax:

(make-bean-data-binding <object> <property> ...other args...)

This kind of binding uses Martin Fowler's Presentation Model pattern as implemented by JGoodies Binding. You implement, in Java, a suitable subclass of PresentationModel (in simple cases, you can just use the base class provided by JGoodies); you then bind a widget to a model returned by an instance of this class for a bean property. Example:

(defvar *presentation-model* (new "my.presentation.Model"))

(text-field :text (make-bean-data-binding *presentation-model* "myProperty"))

The presentation model acts as a glue between the GUI and the application logic, and provides advanced functionality (e.g. it lets you control when to synchronize the state). You can tune it with additional arguments to make-bean-data-binding; for example, you can obtain a buffered model with :buffered-p t.

- Binding to a bean property, arbitrarily nested. Syntax:

(make-property-data-binding <bean> <property path>)

This is a convenient way to adapt a pre-existing bean with the binding framework. It connects a property path, which can be expressed in "dot notation"; to properly observe changes, every object which is part of the path must support the standard Java Bean facility for listening to property changes. Example:

(defvar *x* (new "Person"))

(text-field :text (make-property-data-binding *x* "address.street"))

- Binding to a Cells-powered slot of a CLOS object. Syntax:

(make-slot-data-binding <object> <slot-accessor-name>)

You can use this kind of binding to connect a widget property to a slot of a CLOS object using the Cells dataflow library. Example:

(defvar *x* (make-instance 'my-class :my-slot (c-in 42)))

(text-field :text (make-slot-data-binding *x* 'my-slot-accessor))

- Binding to a calculated expression using Cells. Syntax:

(make-cells-data-binding <expression> [writer])

This is useful to bind a widget to a quick-and-dirty Cells expression without creating a class instance specifically to hold it in a slot. You can optionally provide a writer function so that the widget will be able to alter the value of the expression when its value changes. Example:

(defvar *x* (make-instance 'my-class :slot (c-in 42)))

(text-field :text (make-cells-data-binding

*x* (c? (* 2 (my-slot *x*)))

(lambda (new-value) (setf (my-slot *x*) new-value))))

Syntactic sugar

To avoid the verbosity of make-foo-data-binding, Snow provides convenient syntax to cover the most common cases of data binding. You can enable this special syntax by evaluating the form (in-readtable snow:syntax), for example placing it in every source file right after the (in-package :snow-user) form at the top of the file.

This special syntax is accessed by using the prefix $. It covers the following cases:

$foo is equivalent to (make-simple-data-binding foo).$(c? ...) is equivalent to (make-cell-data-binding (c? ...)).$(slot ...) is equivalent to (make-slot-data-binding ...).${bean.path} is a bit more complex. This syntax resembles that of the "Expression Language" used in JSP and JSF. First, bean is used as the name of a bean: the function stored in the special variable *bean-factory* is called with it as an argument to produce a Java object. The default function simply reads and evaluates bean as the name of a Lisp variable, but you can customize this behavior: for example, you can provide a callback that gets the bean from a Spring application context2. Then, once the bean has been obtained, two things can happen: if path is a simple property (i.e. it has no dots) and the bean is an instance of JGoodies PresentationModel, a binding to the property is asked to the presentation model, as by (make-bean-data-binding bean path); else, a property path data binding is constructed, as by (make-property-data-binding bean path-as-list).

What's more?

I haven't covered which widgets are supported and how much of their API is supported. At this stage, Snow is in a early stage of development, so very little of the Swing API is covered. The best way to learn about Snow usage is to look at the examples included with Snow: the debugger (debugger.lisp), inspector (inspector.lisp) and the REPL (repl.lisp and swing/swing.lisp). Also, I haven't talked about how to use your custom widgets with Snow, and probably other things. Drop me a line at alessiostalla @ Google's mail service, and I'll be happy to help you.

Footnotes

- If you really mess things up, you can change the package of the REPL to one where the symbol QUIT is not visible. If you find yourself in this situation, type (ext:quit) to exit.

- Snow provides a convenient Java class -

org.armedbear.lisp.Callback - that you can subclass to create your custom callback function. You have just to implement the appropriate overload of the call method, or alternatively use one of the static methods Callback.fromXXX to create a Callback from several kinds of Java callbacks.